All Hawaii Honors King Kamehameha Each June 11

| News at the Center | Cultures of Polynesia

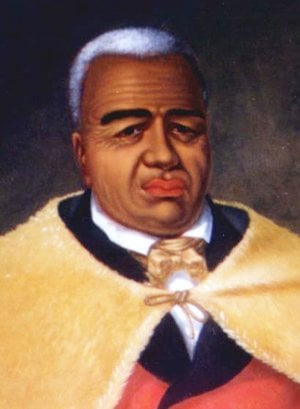

In 1871, King Kamehameha V set apart June 11 as a national holiday honoring his great-grandfather, King Kamehameha I, who first established the unified Kingdom of Hawaii through a series of military victories and alliances with other island aliʻi or rulers between the late 1790s and 1810. When Hawaii became the 50th U.S. state in 1959, Kamehameha Day was one of the first holidays proclaimed by the governor and state legislature.

Today, floral parades, including the famous paʻu or decorated horse riders representing each island, lei ceremonies, hula festivals, and other celebrations continue to mark the state holiday that honors King Kamehameha. For example, various organizations present lei decorations at the famous statue of King Kamehameha across from Iolani Palace in Honolulu, the one depicted in the opening montage of the Hawaii Five-O TV show. The extra-long lei are traditionally draped with assistance from the Honolulu Fire Department.

Other King Kamehameha Statues

Hawaii King David Kalākaua dedicated that statue in 1883, but some people may not realize there are several identical or similar statues, each also recognized on King Kamehameha Day and throughout the year:

- A statue located at Kapaʻau near the ruler’s birthplace in the North Kohala district of the Island of Hawaii. This statue was the first to be cast and was originally supposed to be placed across from Iolani Palace, but it was temporarily lost at sea near the Falkland Islands. Insurance money covered the cost of re-casting another copy from the original in England. Falklanders eventually recovered the original statue, which now stands on the Big Island.

- A third statue was commissioned when Hawaii achieved statehood and was unveiled in the U.S. Capitol in 1969, where it stood alongside Hawaii’s other representative statue, Father Damien of Molokai, in Statuary Hall. After President Barack Obama was first nominated in 2008, the King Kamehameha statue was moved to a more prominent position in Emancipation Hall in the Capitol’s visitor center.

- A fourth sculpture is located at Wailoa River State Recreation Area in Hilo, again honoring the monarch’s Big Island roots. The Princeville Corporation commissioned this statue in 1963 for their resort on Kauai, but the people of that island did not want it erected there since King Kamehameha never conquered the Garden Island. The corporation donated the statue to the Big Island via the Kamehameha Schools Alumni Association, East Hawaii Chapter. It was erected and dedicated in 1997.

- A smaller King Kamehameha statue by the late Hawaiian artist Herb Kawainui Kane stands near the entrance of the Grand Wailea Resort Hotel and Spa on Maui. It is said to be the most lifelike representation of the king compared to the Roman or European styling of the others.

- A sixth version can be seen in the Hawaiian Marketplace on the Strip in Las Vegas.

After the overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, Kamehameha Day continued to be a holiday, although without traditional celebrations. When Hawaii became a U.S. Territory in 1898, Prince Kuhio restored the Royal Order of Kamehameha, re-established the celebration in 1904, and privately observed celebrations until 1912, when the Order began collaborating with other organizations. This eventually led to the modern observation of the holiday on each of the islands and in remote locations.

While the Center’s Hawaiian Village does not stage a specific Kamehameha Day celebration, the Polynesian Cultural Center has participated in the parade, hula contest, and other activities in the past. More importantly, our host island village represents the historical period familiar to King Kamehameha.

Hawaii Islands manager Kaipo Manoa explains that the PCC’s Hawaiian Village includes a hale aliʻi (chief’s house) where the high chief lived. The chief’s house was physically elevated above the rest of the village to signify his importance. There is also a men’s eating house (hale mua), where men ate separately from women and children, and structures designated for specific activities such as fishing and weaving. The village is laid out according to the historical concept of an ahupuaʻa or land division, which included forest, agricultural, and ocean resources, representing everything people needed in ancient Hawaiian culture.

Manoa also noted that soon after the death of Kamehameha I in 1819, his immediate successors overthrew the old kapu or religious system that governed daily life for centuries.

“So, when you visit our Hawaiian Village,” Manoa said, “in some ways it is like stepping back into historical Hawaii.”

About the Author

Mike Foley has worked off and on at the Polynesian Cultural Center since 1968. He has been a full-time freelance writer and digital media specialist since 2002 and had a long career in marketing communications and PR before that. He learned to speak Samoan as a missionary before moving to Laie in 1967, and has traveled extensively throughout Polynesia and other Pacific islands. Foley is mostly retired now, but continues to contribute to PCC and other media.