PCC Hawaii Village Native Plant Displays: Species, Stories & Significance

The Hawaiian Island chain courtesy of smithsonian.org

The Hawaiian Islands are an archipelago of 8 major islands and multiple small outcroppings. They are considered the most isolated land mass on earth. Very few native plants have survived the invasion of foreign ornamental and crop vegetation.

The Hawaiian Island chain courtesy of smithsonian.org

The Hawaii Village at the Polynesian Cultural Center is honored to tend and present Hawaiian-based plants. Here is an overview of just a few:

Medicinal Plants

Growing alongside the Hale Hana (Work House) is a bush that hosts small purple flowers. This plant, called the Awōwī, is utilized as a poultice for mending bones. It can also be ingested as a tea. Awōwī is native to Hawaii, and as is common in tropical plants, it blooms constantly.

Many of our guests are intrigued when they come across a large bottle full of fermenting fruit propped in a tree close to the Hale Lawai’a (Fish Hut). The fruit is from the Noni tree. Its health benefits are well known. It has an extremely bitter and unpleasant taste, so you may want to think twice before you pick one up and take a bite!

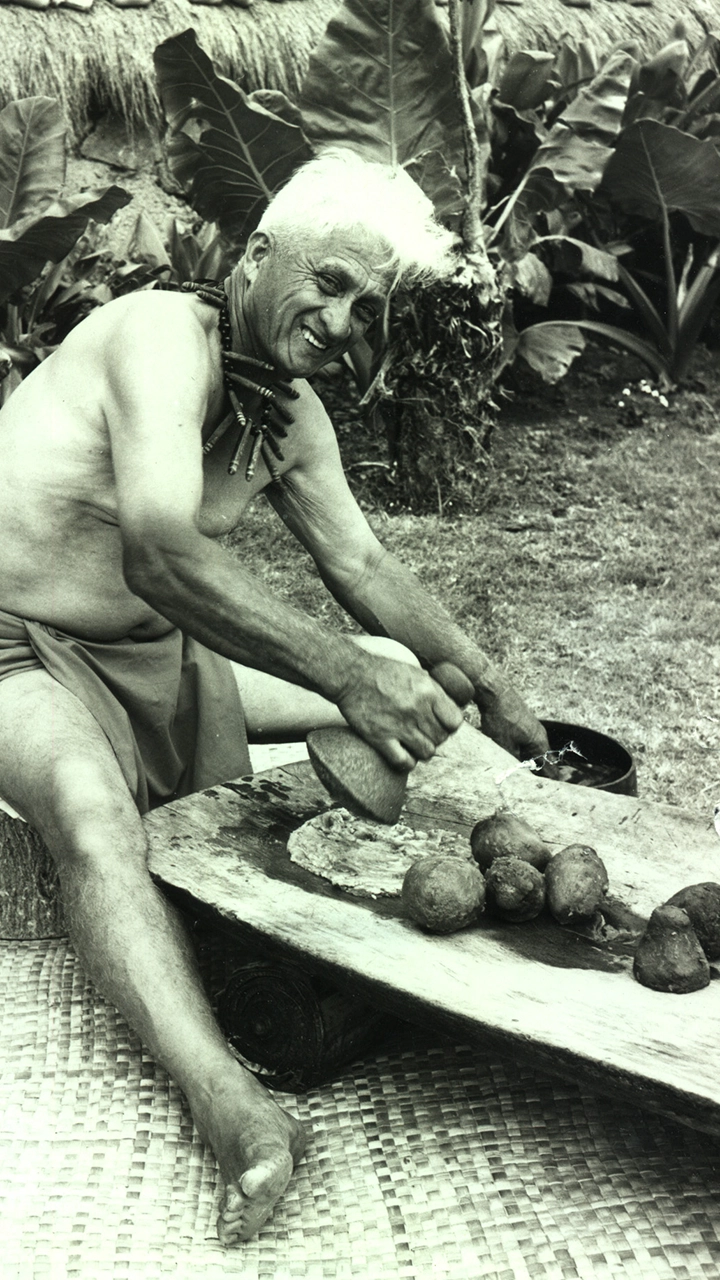

Poi – From garden to table

The hale wa’a, or Poi House, at the Polynesian Cultural Center is used to demonstrate how the Hawaiian staple food, poi, is made: Poi starts as the root of the kalo or taro plant, which comes in two basic varieties: wetland and dryland taro. The PCC grows its wetland kalo in a flooded patch next to the hale wa’a. When harvested, the root is cleaned and set aside to make poi. Young kalo leaves are boiled and used like spinach. The plant stems are replanted, and take from six-to-12 months to grow a new corm, so it was common in old Hawai’i to rotate the planting of different patches to ensure a continuing supply of poi.

The harvested kalo must be thoroughly cleaned, peeled or scraped and cooked for several hours to eliminate the oxylate crystals in the outer layers. If not property prepared, these crystals will irritate and prickle the throat. The kalo is then placed on the poi pounding board and mashed and kneaded with the stone poi pounder, while slowly mixing it with water until the required consistency is achieved. As it was typically eaten with fingers, Hawaiians traditionally classified poi according to how many fingers were required to lift a dab out of the calabash: One-finger poi being the thickest, and 3- or 4-finger poi rather thin and runny in consistency. Hawaiians also sometimes made poi out of breadfruit.

By the way, poi is usually not eaten alone but as a staple food to be flavored with meat or fish. Because dryland taro is relatively sweet and delicious, it is sometimes baked in an imu and eaten whole, but is usually made into poi, which is still very popular in Hawai’i and can be purchased pre-mixed in plastic bags in most local grocery stores.